Are UK house prices vulnerable to rising interest rates?

With interest rates on the rise what could this mean for house prices and market dynamics?

7 minutes to read

Last year, despite inflation starting to tick upwards my assessment was that the UK housing market wasn’t vulnerable to rising interest rates.

Fast forward 12 months and the inflation story is dominating the macroeconomic landscape, pushing interest rates higher, including a 0.25% hike to 1% today, so where are we now?

UK inflation hit 7% in March 2022 and the consensus is it will peak at 9% this year before dipping. However, while the outlook may have changed, several of the reasons put forward in our previous piece still stand. Using Knight Frank Research and insights from Oxford Economics, we take a look at the arguments then and where they stand now.

Lenders could absorb a rise in interest rates

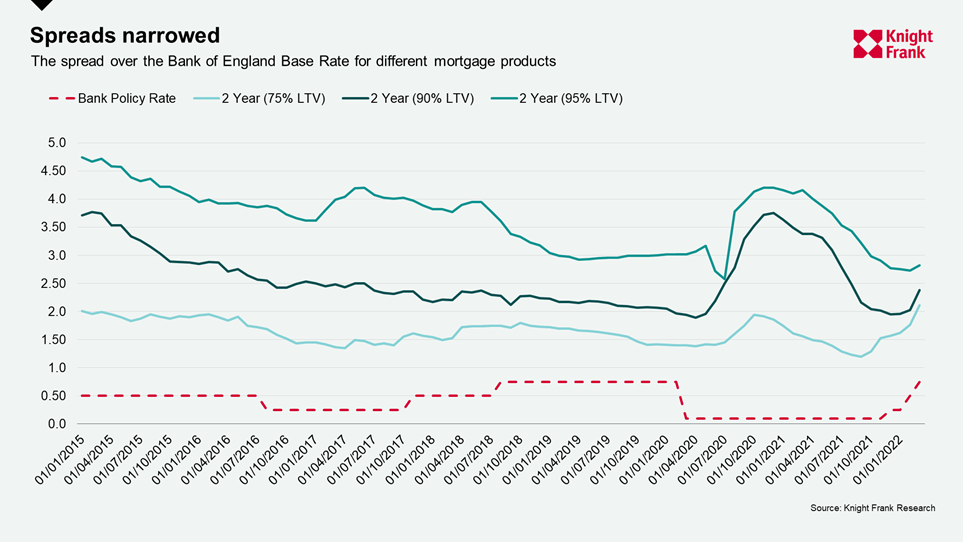

Then: Bank margins, the difference between the base rate and the rate on mortgage products – also known as the spread – were well above pre-pandemic norms at the beginning of 2021. The argument was that base rate increases would be absorbed by narrowing the spread having little impact on mortgage rates.

Now: In reality, margins narrowed in 2021 with competition for mortgages taking lending rates to historic lows in November 2021 – below 1% for some products. Whilst the spread for lower loan-to-value (LTVs) remains below the pre-pandemic level, at 1.36% in March versus the five-year pre-pandemic average of 0.92%, for higher LTVs the spread is much narrower.

The verdict: Spreads have narrowed with rates rising steadily. This means lenders will have less capacity to absorb a rise in interest rates, particularly if they’ve hiked further and faster than anticipated. However, stiff competition among lenders could lead to smaller margins and rate rises not being fully passed on to consumers – particularly for higher LTVs where there is more room for spreads to remain higher than historic averages. In addition, competition is not just coming from traditional banks but also challenger banks, such as Revolut or Monzo, and in general banks are much better capitalised than they were before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

If rates rise, borrowers would still be spending a smaller proportion of their income on mortgage repayments relative to historic norms

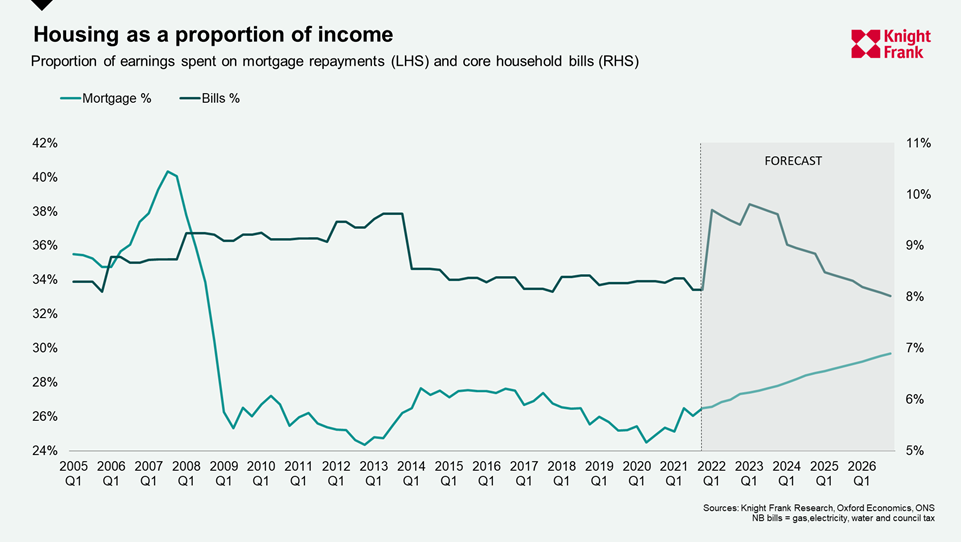

Then: Using a simple model of average lending rates, average incomes and house prices, we know that borrowers are spending approximately a quarter of their monthly income on mortgage repayments. This was compared to almost 50% in the time preceding the GFC.

Now: With cost of living rising as energy costs surge, we have revisited our previous analysis. Utilising our latest house price forecasts and Oxford Economics forecasts for mortgage rates and wage growth, the proportion of income spent on servicing a mortgage is expected to rise to 30% by 2026.

In terms of incomes, forecasts from Oxford Economics suggest that “core” bills will rise from a little over 8% of earnings to 10% this year and into 2023. However, this should fall back as energy prices normalise and pressures on global prices caused by supply bottlenecks fades.

The verdict: Although budgets will be squeezed in the short-term – servicing a mortgage and bills will rise to almost 38% of incomes by 2026 from a low of 33.2% in 2020 – mortgage affordability in the longer-term is unlikely to be affected. One word of caution, however, the recent upward revisions in interest rate forecasts could see incomes squeezed further.

High LTV lending has shrunk

Then: Regulations introduced in the wake of the 2008 GFC resulted in banks cutting riskier 90% LTV lending to about 4% of total mortgage debt in 2020. In 2007, the corresponding figure was almost 16%.

Now: For the most recent 12-month period to end of March 2022 the proportion of mortgages with an LTV of over 90% was around 3.25% and the proportion with LTVs of less than 75% has risen, albeit marginally.

The verdict: This holds even more true. Even if house prices were to fall, there is a smaller part of the market vulnerable to modest declines in house prices, meaning there is less systemic risk. In short, banks have the capacity to incur some credit losses if the most indebted households were to fall into arrears. Added to which the level in value appreciation over the last two years lowers the risk of negative equity/distress of homes purchased prior.

Demand outweighs supply in global housing markets, underpinning prices

Then: A mass reassessment of housing need during the pandemic, an historic supply/demand imbalance and a glut of savings accrued during successive lockdowns will support prices in the short to medium-term, cushioning any blow from increases in interest rates.

Now: The imbalance in markets pushed annual house price growth to 14% across the UK in March 2022. The underlying dynamics have not materially shifted and, even though we expect price growth to cool in the latter half of 2022 and 2023, we don’t expect a reverse.

On the demand side there has been little let up in the early months of 2022, with the number of new prospective buyers across the UK 53% higher than the five-year average in Q1 2022, according to Knight Frank data. We expect this to ebb as mortgage rates rise, the cost-of-living squeeze intensifies and price growth cools as more properties are brought to the market.

Supply in the second hand market has been improving gradually. The new instructions indicator published by the RICS turned positive for the first time in twelve months in March 2022. However, build cost inflation is likely to act as a constraining factor for new housebuilding.

The verdict: There remains a market imbalance and whilst we expect demand to soften as mortgage rates rise, the cost-of-living squeeze intensifies and price growth cools, this will not lead to price declines.

Any rate rises are likely to be gradual

Then: In the wake of the GFC it was 2016 before the Bank of England (BoE) moved rates, lowering them in response to the Brexit vote. A year later they rose 25bps, followed by another 25bps 15 months later. The BoE tends to move cautiously – especially compared to its US counterpart, which began raising rates in 2015 and subsequently raised them 225 bps in three years.

Now: A year on, and the landscape is different with inflation reaching multi-decade highs. The headline measure reached 7% in March 2022 and is expected to rise above 9% in April when the energy price cap rises. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) now expects a peak above 9% in the fourth quarter if the energy cap again rises in October, as is currently planned.

The BoE has implemented three back-to-back rates rises. A further 0.25% hike was announced today, raising interest rates to a 13-year high at 1% and there may be another hike in June. Earlier in the year the expectation was for a cycle high at 2% in 2023, this has now been pushed to at least 2.5%. The Ukraine conflict means they may take a more dovish approach.

The verdict: Whilst 2% is a rate not seen since before the GFC, it’s worth noting that prior to the financial crisis rates had never been below 2%. Whilst rates will rise in the near-term, the cost-of-living squeeze may see the BoE pause for breath to see the impact of rate hikes feed through and not continuing at this pace. A more dovish stance from the BoE is increasingly evident, with meeting notes suggesting inflation would “right itself" and only "modest" tightening of monetary policy required over the coming months.

What has changed?

Twelve months on from my initial assessment, some of the points have softened or no longer prove compelling, such as lenders absorbing interest rate rises.

However several factors, including elevated mortgage lending margins, robust demand relative to supply and a greater proportion of lower LTV lending, means the UK housing market is still in a relatively robust position.

However, if the hawkish tones take hold and we see interest rates rise faster than anticipated and above current estimates this position may shift and weigh negatively on transactions and prices. Data published over the next three months will be fundamental in determining the UK’s economic outlook.

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up here to keep up to date with our regular updates.