Circularity in retail and real estate implications

What could a more circular retail economy mean for retail property?

6 minutes to read

And is it necessarily the threat to physical stores it is perceived to be? I teamed up with Emma Barnstable to look at this exact question.

Recommerce on the rise

The UK's recommerce market, the buying and selling of second-hand goods or ‘reverse commerce’, is currently valued at approximately £6.5 billion and is expected to nearly double to £12.4 billion by 2028, according to research by MPB and Retail Economics. Fashion dominates this market, accounting for 37%, followed by home & furniture at 30%, and tech at 20%, with leisure items making up the remainder.

The research, based on consumer surveys from August 2023, involving 6,000 households across the UK, US, France, and Germany, found that 57% of respondents had bought and 32% had sold second-hand goods regularly. In the UK, these figures are 61% and 32%, respectively.

The cost-of-living crisis is a significant driver of this trend, but sustainability concerns also play a crucial role. According to research by Barclaycard and Development Economics, 62% of UK consumers are more cautious about purchases due to cost-of-living concerns, while 44% cite sustainability concerns as their reason for switching to second-hand.

The trend is especially strong among younger generations, indicating potential long-term growth despite short-term financial pressures. According to the MPB and Retail Economics study, 84% of Millennials (aged 30-44) participate in the used market, compared to 59% of Boomers. Similarly, Barclaycard and Development Economics report that two-thirds of Gen Z consumers prefer second-hand items over new ones.

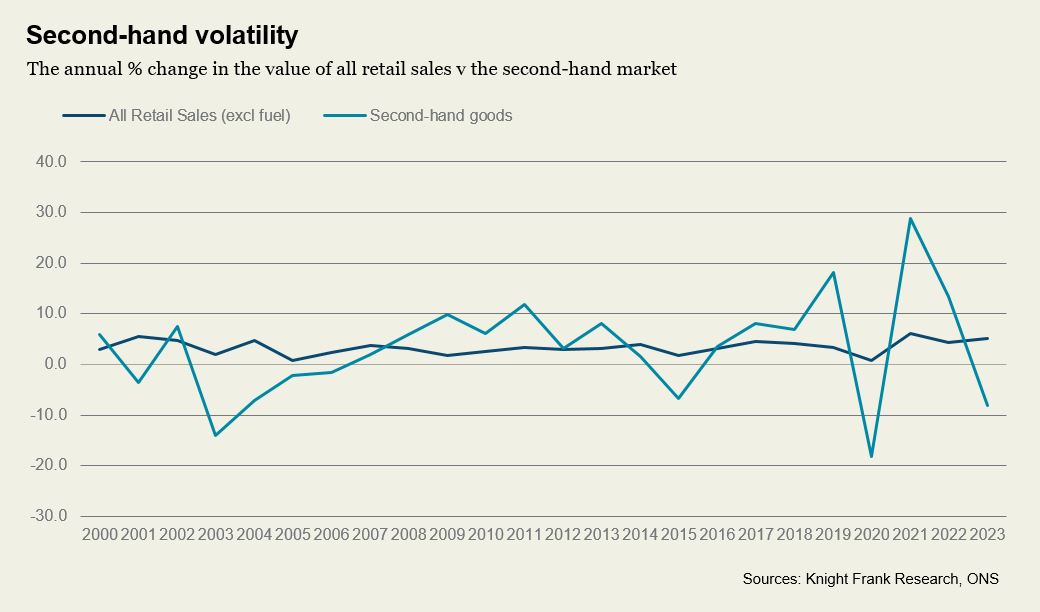

But do consumers always practice what they preach? While sentiment often diverges from actual spending patterns, UK second-hand sales figures reveal a significantly more volatile market compared to the relative stability of overall retail sales. Notably, there was a sharp decline in second-hand sales in 2023, decreasing by 8.2%, contradicting consumer sentiment, and throwing into question economists' expectations of behaviour during times of crisis. This discrepancy highlights the importance of exploring the intricacies of the second-hand market to fully grasp its driving forces and consumer dynamics.

Real estate implications

Concerning purchasing preferences, 90% of respondents to the MPB and Retail Economics survey favour online channels for buying used goods, while just over half (51%) opt for bricks-and-mortar stores. The rise of second-hand shops, including Sweden's second-hand mall, suggests potential revitalisation for high-street retailers. Barriers to second-hand shopping, such as concerns over cleanliness and quality, can be mitigated through in-person shopping. Physical retailers could generate an additional £850million by selling refurbished/repaired technology, according to a study by Trojan Electronics.

The second-hand market can complement and not detract from the new goods market. To have second-hand goods, there must first be new goods, and many companies have shown that repairing and recycling can enhance brand value. Patagonia, with its lifetime guarantee and 24 hour repair portal, exemplifies this, successfully maintaining brand success while reducing demand through a community-based approach.

The opportunity and sustainability benefits are increasingly recognised, especially in electronics—a sector where the UK, generating the second highest amount of electronic waste per capita in the world, could improve. Retailers like Currys advocate for a ‘refurbished revolution’, with 75% of survey respondents expressing concern about e-waste. Currys, along with Music Magpie, AO, eBay, and emerging platforms like Back Market, emphasize the value and sustainability of second-hand electronics, encouraging the circulation of tech products for longer.

Big brands commit

Selling second-hand items in physical stores could become a fruitful avenue for retailers seeking to reduce the environmental impacts caused by their online returns —a strategy Amazon has explored with temporary pop-ups. Its 'Second Chance Store' in Brunswick Centre, Bloomsbury, sold high-quality returned goods, ranging from household appliances to books and games at discounts up to 50%. Although initially an experiment to gauge customer interest, this strategy demonstrates potential as a sustainable and profitable method to address the costs associated with online returns. Amazon now estimates that the second-hand shopping market in the UK is worth at least £1 billion to them.

Mainstream retailers are increasingly testing the value-add of second-hand to stores, whether that be for new revenue streams or to enhance customer loyalty. IKEA's successful buyback and resell program, offering vouchers up to £250 for used furniture, reflects rising consumer interest. In FY23, the program saw a 187% increase, with over 52,000 items re-sold, providing insights into which products are viable for resale, and consumer response to pricing strategies. Although not yet a major profit source, IKEA values the scheme for bolstering customer loyalty and underscoring its commitment to sustainability and affordability.

It will be fascinating to watch major retailers like IKEA and Amazon delve further into the potential of second-hand in-store. Their role in sharing learnings will be key to elevating second-hand shopping from a niche to a commonplace consumer practice, not only improving the appeal of purchasing pre-owned goods, but also offering consumers a second chance at acquiring sought-after products previously missed from their beloved brands.

Over and above environmental and brand-enhancing issues, recommerce could even be a commercial opportunity for retailers. This may appear counterintuitive – after all, heavy consumerism is the cornerstone of retail, the more product retailers are able to sell, the better. But recommerce doesn’t necessarily break nor disrupt this model. The only thing that it changes for retailers is what they are selling isn’t necessarily brand new in each and every instance. Is selling a second-hand item any less profitable than selling a brand new one? No, A second hand item may have a lower price point, but the gross margin may actually be higher. In effect, retailers may be sourcing and selling a higher margin product through a more cost-effective supply chain process. A rare win-win situation.

However, for retailers, As Emma and Stephen Springham point out, there remain significant environmental and social challenges.

Logistical demand

There are broader implications for real estate, particularly the logistics sector as Claire Williams shares. Reverse logistics, which is the movement of goods from customers back to sellers, is a key part of recommerce.

Additional processes associated with receiving, sorting and preparation recommerce. involved with resale before the items can be picked and packed and sent to the customer. As a result, this type of retail requires more space, and more labour than traditional retail or ecommerce logistics.

The growth in recommerce will require supply chains to be more agile and flexible and this will mean more outsourcing to third party logistics firms that have expertise in handling reserve logistics. Unlike brand-new products which follow a predictable route from manufacturer to distribution, resale items often undergo complex routes involving multiple intermediaries.

There are implications for specification of facilities. Unlike standardised formats like pallets or roll-cages used for traditional retail products, used items utilise non-standardised packaging and labelling. This can make the implementation of automation and the use of racking more difficult and requiring bespoke supply chain management solutions for inventory management. With less automation and minimal racking requirements, this type of logistics will have lower height requirements compared with traditional fulfilment centres. Older warehouse buildings that don’t meet the requirements of modern distribution firms could be utilised for this type of operation.

Overall, the circular economy is not one to be overlooked for implications for retailers, retail property and wider logistics supply chain. As well as aiding the UK’s transition to a lower emission economy there are opportunities for existing brands to boost physical retail locations as well as enhance their consumer loyalty and improve their own environmental footprint.