Canary in the coalmine? The bond yield spike and implications for property

After a sustained period below 1%, the ten-year bond yield has jumped up sharply in recent months begging the question as to what this means for property.

10 minutes to read

In the midst of a synchronised global downturn, bond yields plumbed new depths during 2020. Yields were driven down by several inter-related factors, starting with a rapid shift in expectations for the economy and a widespread view that low inflation and substantial spare capacity would persist for some time, leading to a protracted period of low short term interest rates.

On top of this, investors understandably sought the security of government debt at a time of huge uncertainty, with central banks adding to the weight of demand and in Australia’s case, the RBA going further and specifically announcing a target yield for the three-year bond.

The downward trend actually began well before the pandemic, with the ten year yield dipping below 1% for the first time in the second half of 2019 off the back of base rate cuts at that time, but the virus added new impetus which saw the ten-year yield drop further and range between 0.7% and 1.0% for the remainder of 2020.

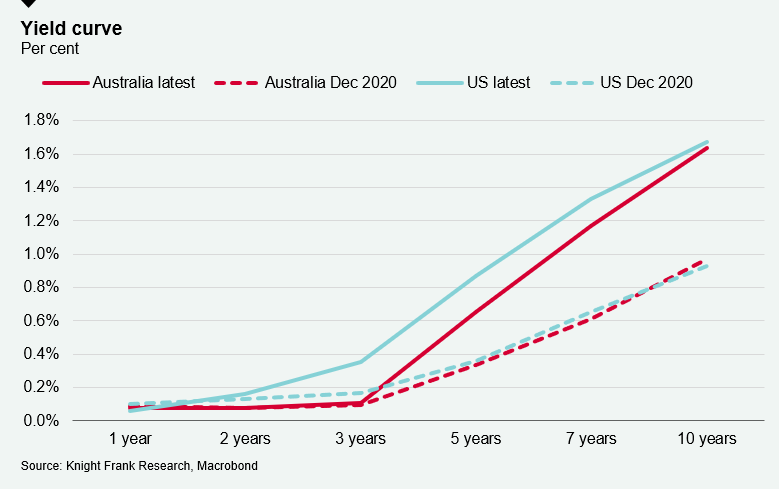

However, 2021 has brought a rapid shift in market expectations and during February the ten-year yield rose dramatically to around 1.8% as a result. The shift in in Australia mirrors the experience in the United States, where the ten-year bond yield has jumped up to sit at around 1.6% compared to 0.9% at the start of the year.

Firming expectations of domestic recovery and policy normalisation

Once more, there are several related reasons for this. Firstly, the gradual roll-out of vaccines globally has led to hopes that the worst is now over for the global economy, with improved prospects for recovery as the year progresses.

Australia has been well ahead of the curve here, having suffered a less severe downturn than other advanced economies and seen a rapid bounce back, with very strong growth of 3.4% and 3.1% in Q3 and Q4 2020 respectively and multiple indicators pointing to sustained momentum this year.

This is leading some market participants to bring forward their expectation for when we will see a normalisation of interest rate settings. While the RBA continues to state that it cannot envisage raising rates until at least 2024, the shift in yields implies that many bond investors anticipate an earlier shift, perhaps as soon as late next year.

US stimulus announcement shifts global outlook and triggers reflation trade

The path of rates in Australia also reflects a reaction to events in the United States. As the world’s largest economy, the path to recovery in the US has global implications and helps to set expectations for the outlook for interest rates globally.

The US has confirmed the rollout of an enormous $1.9 trillion spending package encompassing a broad suite of relief payments to households, businesses, schools and local governments. While it is difficult to compare the exact size of fiscal support in different countries, the latest set of measures means that the combined US response is not only the largest in nominal terms but also among the largest as a share of GDP (estimated at 27%).

The package is so large that it is expected to have a material impact on global growth. The OECD’s March update to its global forecasts saw the estimate for US growth in 2021 raised from 3.3% to 6.5% and a whole percentage point added to projected global growth in 2021 largely as a result.

This package, on top of rapid progress rolling of the vaccine, is leading many bond market investors to rethink the outlook for inflation globally and in Australia. While CPI inflation in Australia has been below the target band of 2-3% for much of the time since 2014 – averaging 1.6% over the past six years – some consider that a rapid and synchronised recovery will be enough to expose supply constraints and drive a sustained rise in wages and inflation.

In turn, this shift in inflation expectations, coupled with expectations of strong growth has brought forward the expected timing of base rate rises and caused long term rates to rise globally including in Australia.

Rise signals improved prospects and hence reduced risks to property income

The rise in bond yields is an important signal and has several implications for property. Firstly, it reflects the strength of economic recovery which means landlords are less exposed income risk than would be the case if the economic recovery was weaker and had been more protracted. Stronger sentiment associated with the more rapid recovery will likely drive a quicker return to CBDs and a pick-up in tenant demand in office markets, while industrial markets will benefit from a sustained rise in household spending. Improved sentiment is also likely to underpin the nascent recovery in business investment, which could in turn, spur a further strengthening in demand for space across multiple property types.

Continued upward trend looks unlikely, limiting threat to property yields

However, the attention of investors will focus more on the implications of higher bond yields for pricing and property yields. It is well understood that rising long bond yields could presage rising borrowing costs and result in upward pressure on yields, despite the positive effects of a stronger economic recovery on tenant demand.

The potential for this negative impact depends on the extent and durability of the change. On this critical point, it is unlikely that the selloff in the bond market has much further to run. Indeed, bond yields have fallen back a little from recent highs. Higher bond yields have been driven expectations of higher growth and inflation than previously anticipated. However, inflation remains low in major advanced economies partly due to structural factors such as the more rapid pace of technological innovation, greater competition in goods markets, and changes in global labour supply that transcend the economic cycle.

Inflation pressures are likely to rise modestly in the near-future reflecting a combination of Covid-related supply chain disruptions and large-scale government stimulus. However, the rise will likely be largely transitory as the impact of supply chain disruptions and government stimulus fade. The structural factors mentioned will also continue to exert downward pressure on inflation as they have over the past few decades.

Despite the stronger economic recovery, major advanced economy central banks have maintained their guidance that monetary policy will remain very accommodative for some time reflecting expectations of ongoing low wage growth and subdued inflation.

Last month, RBA Governor Philip Lowe noted the bond market was pricing in a possible increase in the cash rate as early as late 2022 and then again in 2023, but he said this was ‘not an expectation that we share’, and re-iterated that the cash rate is very likely to remain at its current level until at least 2024. Dr Lowe emphasised that wage growth would need to be ‘materially higher than it is currently’ for inflation to be sustainably within the target range and would require a ‘tight labour market to be sustained for some time’.

Despite the much stronger than expected recovery in the labour market in recent months, the unemployment rate, at 5.6%, implies there is still considerable slack in the labour market, and remains well above levels that would generate sustained upward pressure on wage growth (estimated to be around 4%) and inflation.

Smaller yield shift for shorter maturities

Reflecting the general view from central banks that monetary policy will remain very accommodative for at least several years, shorter-dated bonds have been less impacted by the selloff. The 5-year Australian government bond yield has risen by 42.5 basis since November compared to 90 basis points for the 10-year tenor, while the 3-year yield has not risen at all due to the RBA yield target. This is an important consideration for property given that most of the debt secured against property is on these shorter terms.

Remembering the ‘taper tantrum’

Central bank guidance will likely restrain any further rise in bond yields and may even lead to bond yields falling back again if financial markets come to the view that the selloff has been premature. The sell-off in bond markets in 2013 commonly known as the ‘taper tantrum’ is good example of how a sharp rise in bond yields can be subsequently unwound in a relatively short amount of time.

The 10-year US Treasury yield rose from 1.66% on 1 May 2013 to 3.04% at the end of 2013 after then Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke flagged the central bank’s intention to reduce bond market purchases at some future date. Bond markets then rallied steadily in 2014 and early 2015 as it became clear that low interest rates were still needed, with the 10-year Treasury yield falling back to 1.68% on 2 February 2015. The 10-year Australian government bond yield rose by 135 basis points between 2 May 2013 and 6 January 2014 to 4.38%, before falling by 210 basis points in just over 12 months to 2.28% in early February 2015.

Property yields to hold firm, but further yield compression has a limit

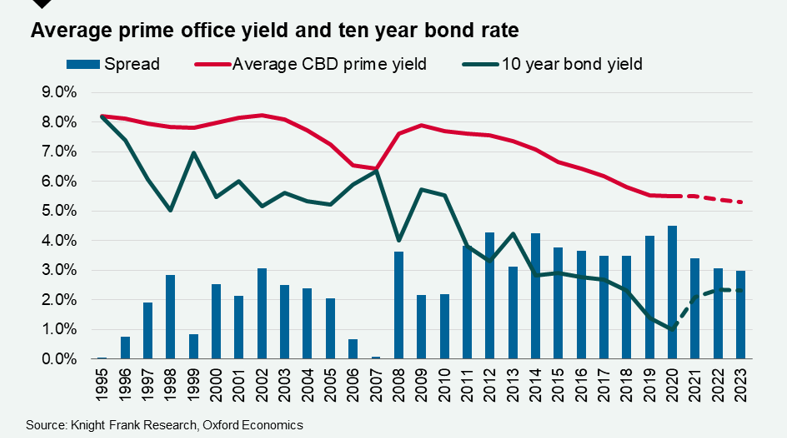

The change in longer-dated bond yields is significant but interest rates remain very low. Moreover, property yields had not entirely adjusted to the shift to lower interest rates since 2019. Even with the recent sell-off in bond markets, the spread between prime office property yields in the major capital city CBDs and the 10-year government bond yield is close to 400 basis points, well above historic norms by any measure.

The fact that the spread is still this high indicates that most property market investors expected that interest rates would increase eventually; it has just happened sooner than expected. While views will always differ on long term equilibrium levels, property pricing is driven by medium to long term trends and the market has a slower process of price adjustment compared with bond and equity markets, which serves it well in these periods of market volatility.

Because of these factors, the outlook remains much the same as it was before. Prime office yields are expected to hold firm this year with a greater than usual divergence in the performance of individual assets. Yields on higher quality prime buildings and assets with longer income streams may potentially tighten further and indeed this is our expectation in 2022 on the basis that occupier markets will see improved momentum off the back of rapid employment growth and, for some businesses, the desire to upgrade space to meet new workplace needs post pandemic. Our forecast is for the average prime yield across the major CBDs to compress from the current 5.5% to 5.3% by end 2023. On the other hand, secondary assets and assets with less secure income streams will face greater pressures.

Meanwhile, in industrial markets, yield compression continues in response to the ongoing lift in tenant demand due to ecommerce and the prospect that the expansion in our major cities’ requirement for industrial floorspace has considerably further to run. Prime yields continue to edge lower and are now closing in on the 4% mark in Sydney and Melbourne for the best assets. With the weight of capital seeking deployment far outstripping the quantum of investable stock, the market looks set for further growth.

However, the recent sell-off in bond markets serves as a reminder of the need to be cautious in assuming that sustained yield compression will continue indefinitely. There is a limit to how low interest rates can go and Australia is a very different and much faster growing economy than the likes of Japan and Germany which experience negative interest rates. Even if it is short lived, the sell-off reminds us that the yield compression we have seen over the past decade cannot be repeated.

For further information please contact:

Ben Burston

Partner, Chief Economist

+61 2 9036 6756

Ben.Burston@au.knightfrank.com

Chris Naughtin

Director, Research & Consulting

+61 2 9036 6794

Chris.Naughtin@au.knightfrank.com