Heating, cooling and running homes? English Housing Survey results

We digest the key energy takeaways from the recent English Housing Survey.

5 minutes to read

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities recently published detailed results from the 2021-22 English Housing Survey (following the headline report in December 2022) including a section on energy.

We explore some of the key themes including the UK's home energy use, the effectiveness of cooling and heating methods, the role of insulation, and the cost implications of upgrading energy performance.

Why does it matter?

For the UK, how we cool, heat, and run our homes will be a pinch point on the road to net zero. In 2022, the residential sector accounted for 17% of all emissions. Admittedly, emissions were 16% lower than the previous year, though a large part of the saving was due to a bout of warmer weather and high energy prices rather than efficiency measures.

The government previously proposed an ambition to have all homes at a minimum EPC C rating by 2035 in the energy efficiency bill in 2021, with the Review of Net Zero by Chris Skidmore proposing to bring this forward to 2033. Yet, there is no set path for implementation – in England and Wales at least, with Scotland still pressing ahead.

Instead, there is evidence of ministers increasingly backing away from green policies. Michael Gove, the housing secretary, has already signalled that landlords will have longer to adapt to rules requiring rental properties to have at least a “C” energy efficiency rating, for example.

The latest release from the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) offers some insight into energy and UK homes. The survey was undertaken at the end of Covid restrictions and prior to the recent energy cost spike and government capping of bills.

Cooling buildings

With this year likely to be the hottest on record globally, cooling our buildings and homes is a key concern and current methods aren’t proving effective, English Housing Survey (EHS) finds.

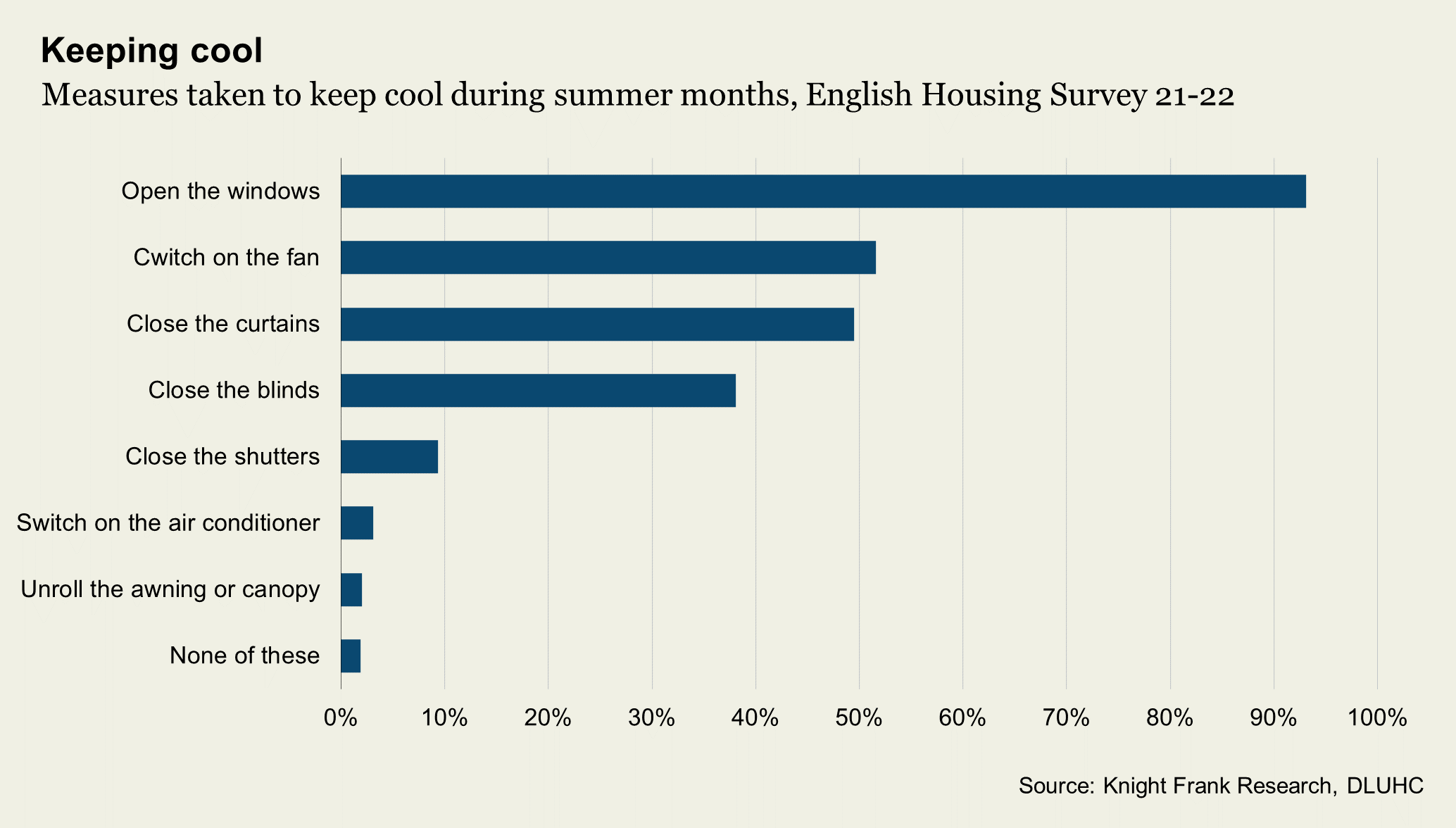

The new data from the DLUHC on energy demonstrates methods currently used to cool homes. The most common, cited by 93%, was opening the windows, followed by switching on a fan (52%), closing the curtains (50%), and closing the blinds (38%), just 3% of respondents stated they switch on the air conditioner (see chart below).

However, opening windows is reportedly not all that successful. Just under half reported that they were ‘always’ able to keep cool in the summer months by opening their windows at night, under a quarter (22%) mentioned that they were ‘often’ able to keep cool, 21% mentioned ‘sometimes’ and 9% said that they were never able to keep cool.

Heating buildings

It's not solely about keeping buildings cool. Our buildings are going to need to be able to withstand more extremes in both directions, and therefore how we heat our homes matters a great deal.

According to EHS data, most homes with a primary heating system present utilised boiler systems with radiators (89%), this was followed by storage heaters (5%), room heaters (3%), communal (2%), and less than one percent had warm air systems or other heating systems. The survey found that in 2021, less than 1% of the stock, or 179,000 dwellings, had a heat pump for space and/or water heating.

Of the 179,000 dwellings that had a heat pump, around three quarters were owner occupied (74%), 15% were owned by housing associations and 8% were owned by local authorities.

The government is targeting 600,000 installations a year by 2028, up from just 55,000 installations in 2021. Even if the market were to grow by a blockbuster 30% every year, the 600,000 target still wouldn't be met in that timeframe, the National Infrastructure Commission said earlier this year.

Energy efficiency

Aside from how we heat and cool our homes, the critical issue is keeping them that way and that requires efficiency and insulation.

Whilst there has been a marked improvement in the overall energy efficiency of dwellings, as measured by their Energy Performance Certificate (EPC), there is still a long way to go. According to EHS data, the proportion of homes rated EPC A to C increased from 16% in 2011 to 47% in 2021 – however, our research earlier this year put the figure a little lower at 44%.

Interestingly, younger generations place greater emphasis on sustainability – though that may reflect the type of housing occupied by different age groups. The younger the Household Reference Person (HRP), the more likely they were to live in an energy efficient home. In 2021, households where the HRP was aged 16 to 44 were more likely to live in EPC band A to C rated homes (54% to 61%) than older households, aged 45 or older (39% to 46%).

One way to improve efficiency and energy use is through monitoring. However, in 2021, fewer than half of households (44%) reported having a smart meter in their home. Whilst this is up from the 39% reported in 2020, there is still a long way to go to ensure greater energy usage management and monitoring.

A recent study by the Data Communication Company found that Britain’s smart meter network is helping to prevent more than one million tonnes of carbon emissions each year, the equivalent impact of one million cars.

How much does it cost to upgrade EPC rating?

A significant barrier to improving the overall energy efficiency of the housing stock is cost. The EHS data estimates the average cost to improve a dwelling to a band C was £7,529, down from an estimated £7,737 in the 2020/21 survey and £8,110 in the 2019/20 one.

Our own analysis of over five years of EPC data puts the figure at over £9,000. Regardless, the total expense is staggeringly high. DULHC estimates that to upgrade all housing stock to a C would require between £89 and £91 billion. Our own estimates put the cost for the private rented sector alone at close to £18 billion.

The survey shows that we are making progress but have some way to go. The more extreme weather events highlight not only the need for more efficient homes but the methods of how we heat and cool them.

Cost remains the most significant barrier and even with an uplift in value for more energy efficient homes or reduction in energy costs, the upfront capital required will continue to mean slow progress is made without either regulation being ‘the stick’ or tax break or other incentives offering ‘the carrot’.

Subscribe for more

Get exclusive monthly ESG property insights straight to your inbox.

Subscribe here