Just William

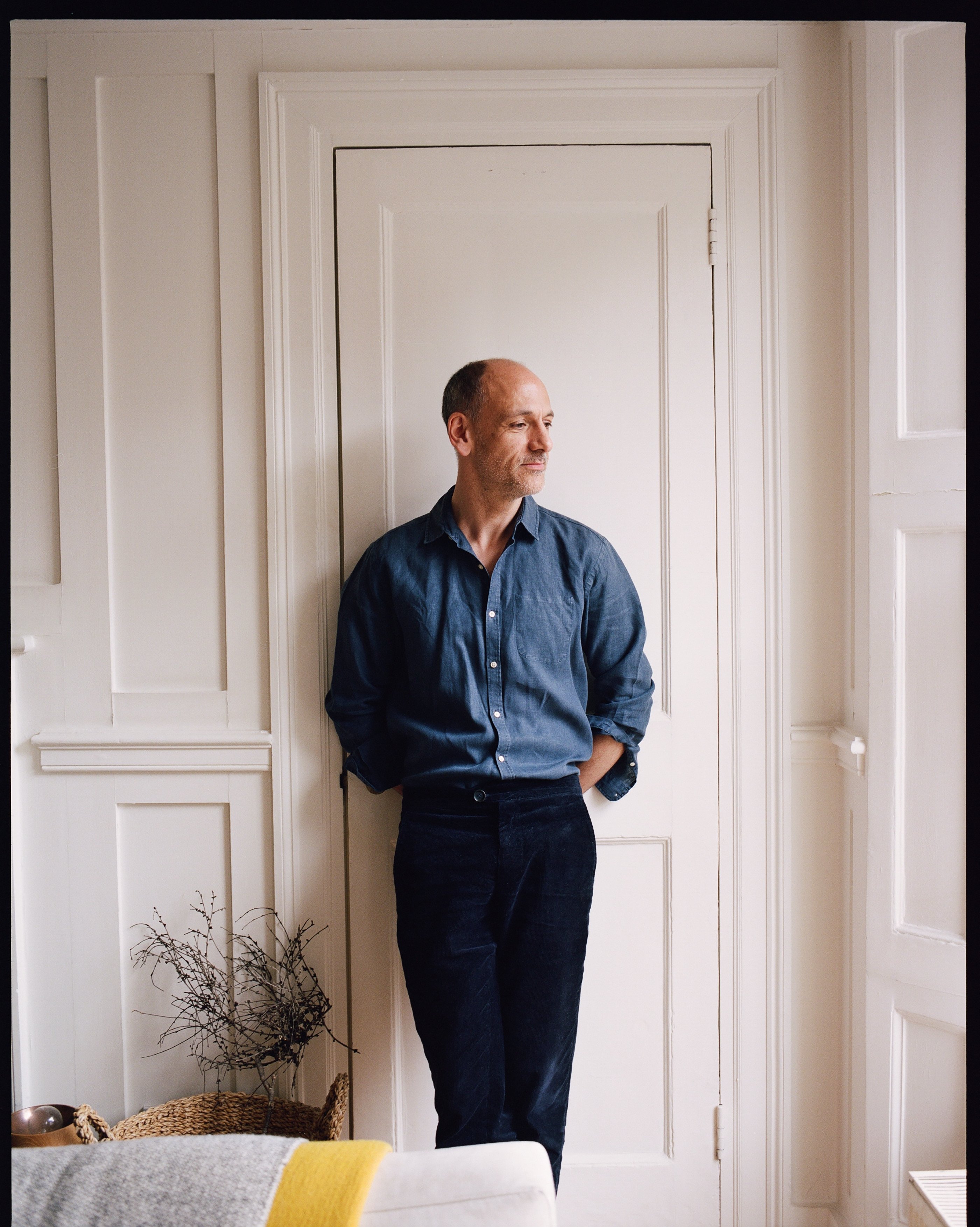

British architect William Smalley is a quiet rebel, an architect who’s concerned not with spaces that shout, but which encourage introspection, quietness and purity of form

Some homes are conceived with a magazine cover in mind, but the work of London-based architect William Smalley seeks to provide answers to more humble questions: what could be the best space to read a book, to listen to music or host supper for close friends?

Mind you, in no way should this undermine the seriousness of his work – or the high esteem in which he’s held. Landscape architect Kim Wilkie describes Smalley’s aesthetic as having “the beautiful clarity and precision of a crisp morning,” while another of this issue’s design luminaries, Ben Pentreath has also written about Smalley’s distinctive language, which combines a reverence for tradition with an uncompromising eye for minimalism.

It’s hard to define Smalley’s work without using the hackneyed expression ‘timeless’, but perhaps ‘quiet’ is a better word. Seated in his study in his Bloomsbury home, linen shirt sleeves casually rolled up, at a desk that once belonged to his grandfather who lectured Alan Turing at Cambridge, he tells me that despite a preference for things which are spare and stripped back, he prefers to be thought of as an “abstract expressionist” rather than a minimalist.

“What I build is concerned with abstract qualities of light, space, views and the juxtaposition of solidity, mass and space. What I’m not about is houses with big glass walls, so when it’s raining outside it feels as if it’s raining inside and there’s no homeliness or warmth,” he says calmly, leaning back into his chair.

The homes he likes most are those that are not outwardly perfect but which most reflect their owners. He rolls his eyes at country houses built with what he calls a “Notting Hill floor”, the sort that doesn’t take too kindly to having a basket of logs dragged over it and which isn’t made from the kind of materials that acquire a patina that gets better with time.

He thinks the best clients understand that building a home is part of the process, to be enjoyed rather than merely tolerated. “Architecture is not found, it is made. It takes time to build a house and for an interior to come together, just as it takes time to craft a beautiful object.”

His first client was Alan Rusbridger, the former editor of The Guardian, whose weekend cottage he remodelled in the Cotswolds. Further afield there is a chateau in the French Alps where he rebuilt the 2,500 sq ft roof to create a cathedral-like space for entertaining, an apartment in New York and and a house in Katamon, Jerusalem. Elsewhere in the British countryside, Smalley can lay claim to Liscombe House – the perfect reinvention of a country house in Buckinghamshire, while in London he’s also remodelled the home of Monocle’s editor, Andrew Tuck and recently, a modernist house on a common in south west London.

As well as residential creations, Smalley’s current projects include 14 Cavendish Square, a cultural event space-cum-gallery in central London, and Woven and Howe London’s new 4,000 sq ft joint-flagship store on Pimlico Road. “Both those buildings are interested in expressing the history of those spaces because they have interesting back stories,” he says. “I see the history of architecture as a continuum, I don’t see a break between traditional and modern architecture. Perhaps that’s because I grew up in a 15th-century house, but really it’s all just architecture and we are answering and problem-solving the same questions: what should it look like and will it be a nice place to be?”

All of his projects are united by a tasteful spareness and a deep appreciation of materials and textures. Longevity is a key consideration too: “I don’t think my work dates because there’s a quietness to it. Sometimes that quietness loses me work because the client wants ‘hot’ and ‘loud’.” However, he’s proud to admit that none of his clients has yet sold their Smalley home.

He likes to be involved in every stage of the process from start to finish and often the real challenge for Smalley is learning not to agonise over every single door hinge. “There’s this control freak element which I suppose architects are wont to suffer from,” he shrugs before scooping up Dylan, his Jack Russell, who settles into the seat of a pink Muller van Severen chair.

His first book, Quiet Spaces, is an exploration of his own work and the buildings that have inspired him; from Casa Barragan in Mexico, to Geoffrey Bawa’s Lunuganga in Sri Lanka, Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, Villa Saraceno in Italy and Roche Court in Wiltshire.

“Most interiors that are published were made to be shown,” he says. “They crave to be seen; extroverts of the interior world. The interiors pictured in the book have the opposite quality: they were made quietly, for private contemplation; introverted spaces that serve their own purpose and feel no need to shout.”

Arranged in four chapters, the book discusses Space, “how we experience this is so personal to us”; Silence, as the antithesis to maximalism; Shadows, “architects talk about light, but really it’s shadows that are our medium, especially in England where everything is shaded and nuanced”; and Life, the disruptor, “allowing people and stuff in” is the final piece in Smalley’s jigsaw. Over a period of two years, he flew to Sri Lanka, Mexico and Italy with photographer Harry Crowder to photograph these houses especially.

Good modern architecture, according to Smalley, allows you to plant a piece of furniture from any period into a house and for it to feel right, “whether that’s a Corbusier, a Mies Van der Rohe, a sculpture or your granny’s kilim rug. There are only a few modern houses where you can do that – where you can really mix things up.”

“If I’ve listened to my clients and worked out how they are going to live, that’s when the house comes to life and works in the way it is intended,” he pauses, “or sometimes unintended, but in a good way.” In any case, a little faith is always required: “It feels easier to aim for perfection than imperfection, because at least you know what you are aiming for that way – but imperfection is the better state.”

As a craftsman, the path that Smalley navigates is a personal one which comes down, he thinks, to intuition – as a sort of building whisperer. He looks coy, before admitting that buildings and spaces sometimes speak to him. “I feel I can go and stand in a field and I know exactly where the building wants to be.”

Quiet Spaces is available now, published by Thames & Hudson, from thamesandhudson.com. Carolyn Asome is a design writer and consultant.