Does hybrid work lower carbon emissions?

With the world of work having been upended and hybrid working approaches increasingly becoming the norm, we consider what this means for emissions, more importantly, does hybrid work really lower carbon emissions?

9 minutes to read

Embracing the global workplace experiment

The Covid-19 pandemic kickstarted the great global workplace experiment, which is far from over as workplace strategies continue to evolve. We have now entered the phase where occupiers have more clarity, better signals of what works and what doesn't, and now seek to reflect changes in work style in their future workplace.

The world of work has undoubtedly changed and will continue to do so. Yet, despite the initial buzz surrounding remote work and declarations that the 'office is dead', this is far from the reality we face. More occupiers are adopting workstyles that, whilst affording some flexibility to staff, position the office as the dominant place of work (in terms of hours/days spent).

According to our recent (Y)OUR SPACE survey, 56% of occupiers consider hybrid as their most likely working style, while 31% still perceive the office as the primary workplace for the foreseeable future through the adoption of office-only or office-first workstyles. With an increasing number of companies adopting this blended approach, does this mean fewer employee commutes and, therefore, lower emissions?

There have been studies suggesting just that. But, if offices are still operating and employees are also using energy at home, does this negate the lack of commuting emissions? Do companies account for this within their scope three emissions or even when choosing where to locate? We examine the ideas below in an attempt to answer the question: Does more flexible forms of work that combine office and remote settings really lower carbon emissions?

Shifting workplace paradigms in the UK

What does the hybrid work style mean in practice? Research shows that in the UK, employees spend, on average, 1.5 days per week working remotely, according to a report by IFO Centre for Macroeconomics and Surveys, which is above the global average of 0.9 days.

This is mirrored by another recent survey of FTSE 100 companies. Of the 100, 14 have transitioned to two days of remote work per week, while eight maintain a two to three-day work-from-home arrangement, and six operate on a two-day in-office schedule. Hybrid is clearly taking root in the UK. This new pattern will have implications for emissions, but there are nuances.

The complex reality of hybrid work

Some critics challenge the commonly held belief that eliminating daily commutes leads to a significant reduction in our carbon footprint. At first glance, it seems like a straightforward conclusion – fewer commutes should mean less pollution, right? However, the reality is much more complex.

In a half-empty office, the need for heating and air conditioning remains the same as in a full one to ensure employees' comfort, which is particularly true given that 79% of office space falls below the EPC B level.

On the other hand, when people work from home, they also consume energy for heating, running technology, lighting, and air conditioning (albeit this is only applicable to a small proportion of homes), among other things. We also know that more than half of residential properties in England currently fall below the potential minimum of EPC C

Is simply giving up the commute a few times a week enough to offset the additional energy used for home comfort? Some argue that this is not the case.

During successive lockdowns in the UK, the average home electricity consumption increased by over 15% on weekdays, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). However, we note that this may not be a true reflection as even those who cannot usually work from home were at home, as well there being increased time spent at home which, under usual circumstances, might be used to undertake leisure or social activities outside of the home. Workers who usually use public transport or those with short commutes of less than 6km each way, might, in fact, increase their total emissions when working from home.

In addition, there may be seasonal differences due to differing energy demands. Office work in winter and home working in summer could lead to an overall reduction in emissions, according to environmental consulting firm WSP. The study estimated that home working in summer saves approximately 400kg of carbon emissions.

However, according to the study, working from home five days a week results in around 2.5 tonnes of carbon produced annually, significantly more than an office worker, mainly due to increased home heating during winter. Albeit this study only factors in commuting emissions versus home heating and electrical demands, not accounting for office energy demands.

Research by Reuters concludes a similar pattern. The study reveals that the emission reduction from commuting is balanced out by the increased energy consumption at home during remote work. While commuting directly contributes to carbon emissions, remote work often relies on digital technology and the internet. Regardless of location of work, ‘hidden’ energy costs through data centres, servers and internet infrastructure contribute to the carbon footprint and this will only increase further with wider adoption of AI.

How then do emissions stack up?

We've analysed the Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) of the office stock across England and Wales. These EPCs estimate an average just shy of 17kg of CO2 emissions annually per sqm for a typical air-conditioned office building over 9,000 sqm.

This equates to approximately 166.3kg of CO2 emissions per employee per year, or around 16kg of CO2 emissions per employee per week, assuming they work in the office full-time. This is based on British Council for Offices guidelines of 10 sqm of space per employee.

In the UK, 68% of commuters utilise cars for their commute. The average daily round-trip car commute covers a distance of 20.9 miles, resulting in approximately 5.5kg of CO2 emissions, according to the National Travel Survey. This brings the total carbon footprint, of commuting and office usage, for full time office workers to 43.5kg of CO2 emissions per employee per week.

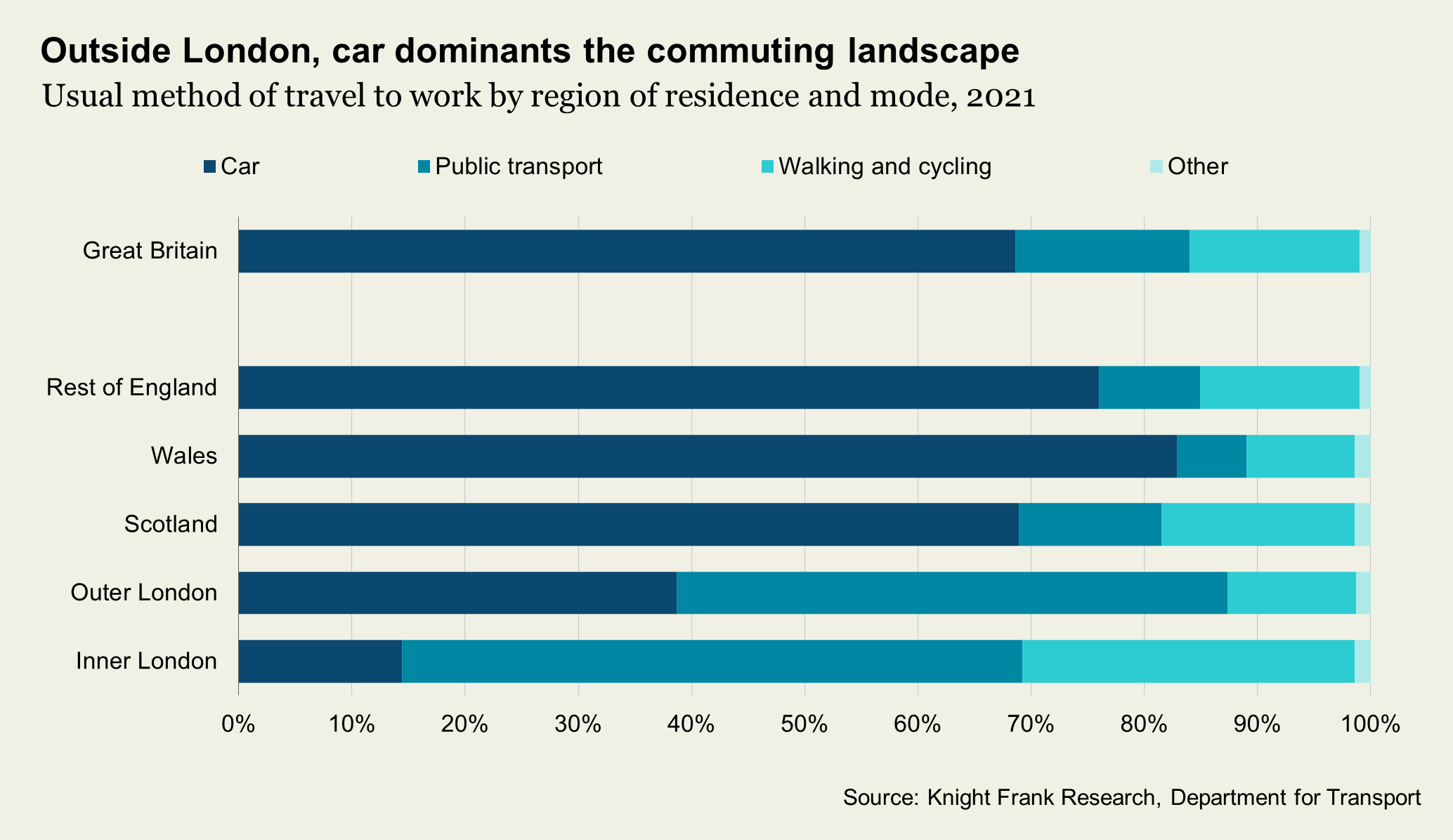

But what about cities where commuters tend to lean towards public transport options? The carbon footprint per commuter might differ substantially from those heavily reliant on cars.

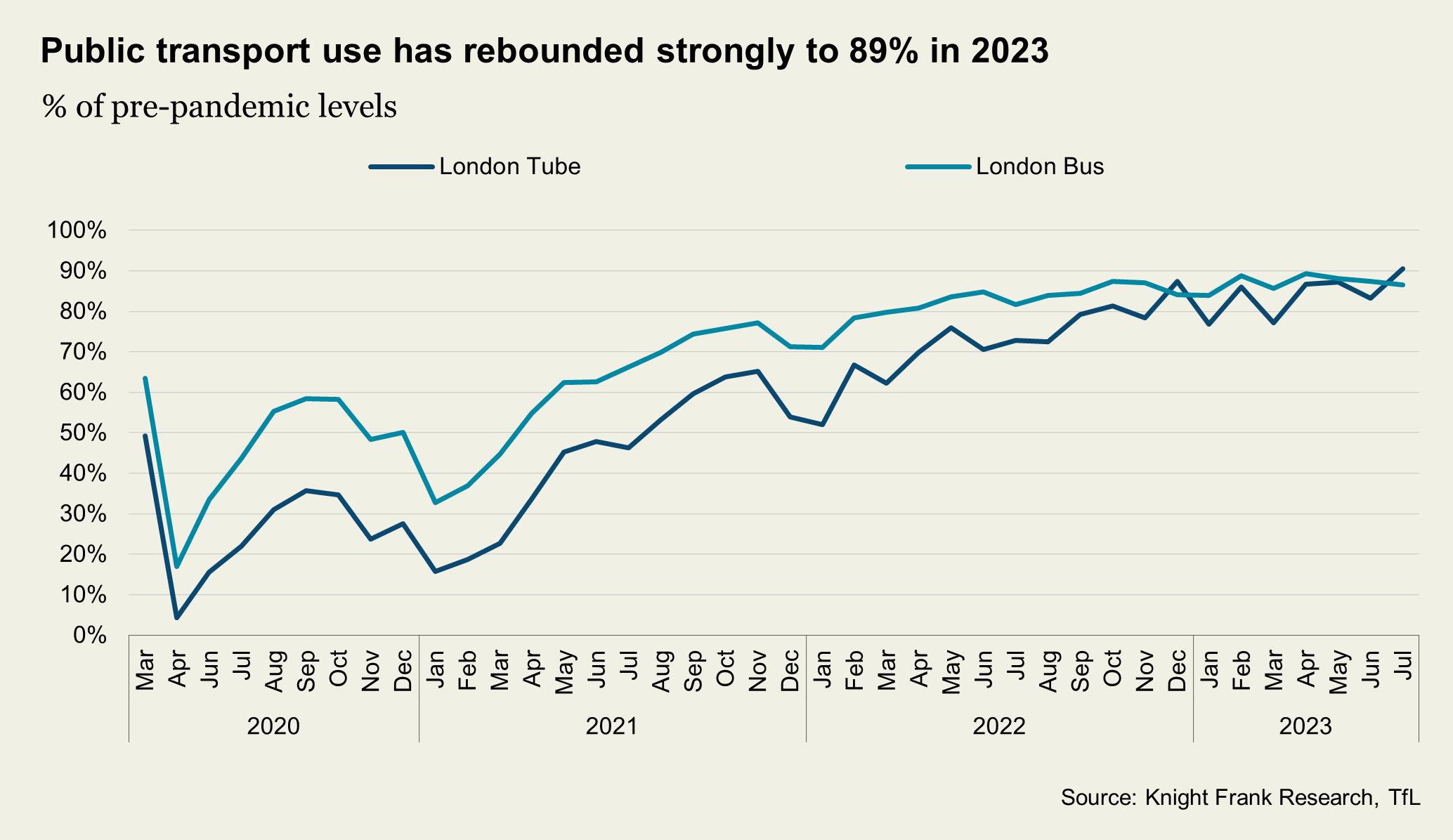

In London specifically, demand for public transport has normalised post-pandemic, as shown in the chart below, leading to the levelling off of Tube and Bus usage since the second half of 2022. The number of Tube and Bus trips in London has now reached 89% of pre-pandemic levels.

Public transport accounted for over half of the commutes in central London in 2021, but this proportion drops to just under half in the Outer London suburbs, according to the Department of Transport. On average, Londoners travel about 8.6 miles to get to work on public transport.

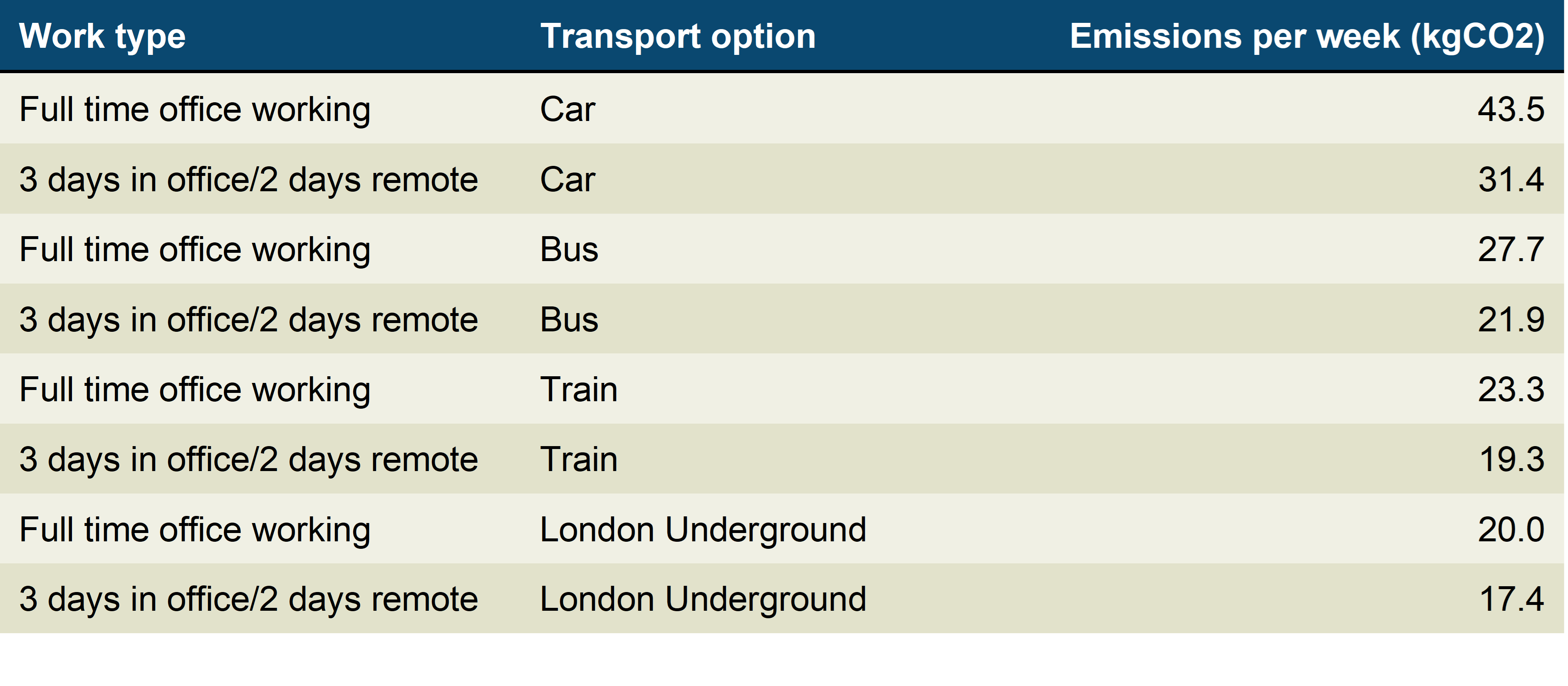

The total carbon footprint for a full-time office worker varies depending on the mode: 20.0kg of CO2 emissions per employee per week for London Underground users, 23.3kg for National Rail commuters, and 27.7kg for those relying on local buses.

But what if an employee's office attendance is limited to three days per week, how do the numbers stack up? Based on the emission conversion factors published by the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS), home working employees generate around 2.7kg of CO2 emissions daily. These factors estimate the incremental energy use from office equipment and home heating by homeworking employees which would not have occurred in an office-working scenario (this includes the assumption that one-third of employees have one household member who would usually be at home during the day).

With the average hybrid work schedule, the emissions are only produced for two days per week at home, resulting in a weekly total of 5.3kg of CO2 emissions. Including the office and car commute emissions, the total becomes 31.4kg of CO2 per week.

The carbon footprint is notably smaller for those who use public transport in London, ranging from 17.4 to 21.9kg of CO2 emissions weekly for London Underground and London Bus users, respectively.

While we have simplified the analysis here, and not considered multioccupancy of homes among many other variables, there are some key points to draw out. It is circumstantial, and the table below illustrates this.

Opting for hybrid working can result in a reduced carbon footprint compared to full-time office work, provided low carbon transport alternatives are prioritised and that home energy efficiency is boosted. On the other hand, if the primary commute option involves higher-emission transport, such as cars, the absence of a commute in hybrid working scenarios may yield greater carbon savings than what is generated in the office. In addition, with a reduced number of commutes in car reliant locations there could be a reduction in congestion and emission through that channel.

Location, location, location

By adopting a hybrid work model, the carbon footprint responsibility might inadvertently shift to employees, who may need to invest in lower-emission infrastructure on their own. While individuals are exploring solutions like installing solar panels, smart thermostats and low-energy lighting, it remains a work in progress.

A potential compromise lies in having employees work remotely from home on specific days. This arrangement benefits companies by reducing office energy usage on those days and minimising energy consumption for empty office spaces on remote workdays.

Companies may also consider downsizing their under-utilised office space to further mitigate emissions, with findings from our (Y)OUR SPACE survey revealing that 23% of surveyed companies plan to reduce their total floor space across their portfolio within the next three years and that this was particularly true of the largest companies (employing more than 50,000 people globally) who responded.

Companies thinking about moving office buildings should also consider what it means for the daily commute. Besides better amenities and the drive to cut carbon emissions through building operations, relocating an office can have an impact on how far employees have to travel each day. If the new office is strategically placed closer to major transport hubs, it could potentially reduce commuting distances for many employees, resulting in lower carbon emissions from daily commutes.

In addition, there are possibilities for advancement in technology and monitoring to make office spaces more sustainable. For example, with new smart monitoring there may be ways of closing part of floors to optimise energy use or potentially make space more concentrated with hot desks and similar, so the energy comparison becomes trickier and far more nuanced.

While hybrid work has become prevalent and many companies have invested in work from home setups, we may need to rethink the full picture of a hybrid work footprint. There needs to be a holistic approach to how companies assess and report on their scope three emissions.

Photo by Marc Mueller