Ukraine war speeds up UK’s agricultural transition

The fall out from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will have a profound impact on food, farming and land use in the UK.

6 minutes to read

Change was knocking on the front door of farmhouses across Britain even before the fateful moment on 24th February 2022 when Vladimir Putin sent his tanks rolling across the Ukrainian border.

Brexit had pulled farmers from the protective, if often stifling, embrace of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) whose subsidies at times accounted for up to three quarters of Total Income from Farming (TIFF) in the UK, while the war against climate change was firmly camped on the nation’s green and pleasant pastures.

The impacts from both of these will have significant long-term consequence for farms and estates, but the change will be relatively gradual, giving the industry time to adapt, or longer to bury its head in the sand, depending on your point of view. Farmers will still receive some kind of area-based subsidies modelled on the former CAP until 2027, while net zero targets imposed on the food chain by retail customers won’t fully kick in until 2035 at the earliest.

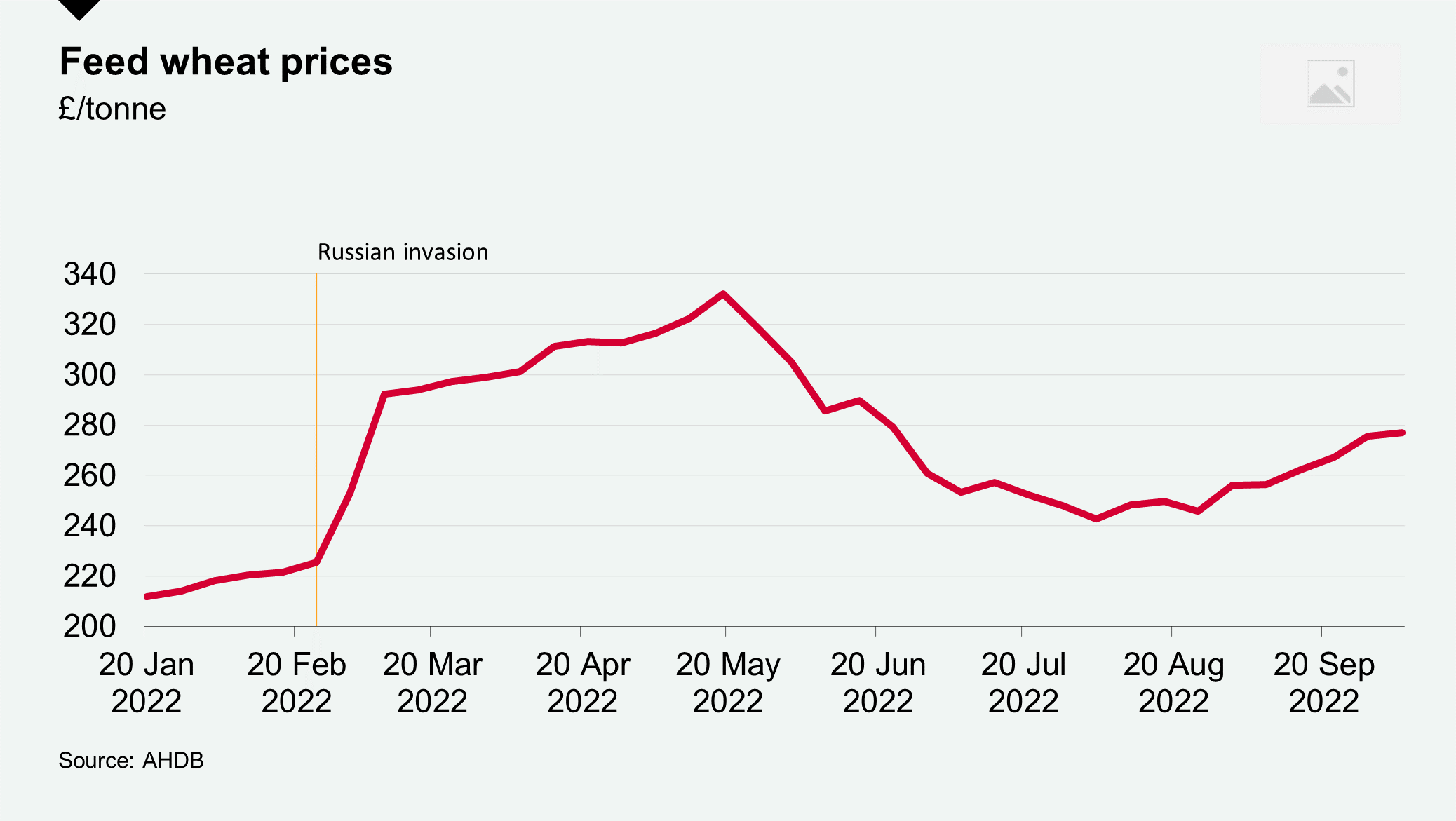

The war in Ukraine has, however, had an immediate effect that could not be ignored. Swift sanctions imposed on Russia and the blockade of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports saw grain, energy and input costs spiral.

While arable farmers briefly saw the price of wheat and oilseed rape go through the roof, the realisation quickly dawned that even sharper rises in the cost of fuel and fertiliser could quickly cancel out those gains.

Livestock farmers, particularly feed and energy-intensive poultry, egg and pork producers, saw far less of the increase in prices, but even more of the downsides and many were quickly fighting for survival – there are even concerns there will be egg and pork shortages by Christmas.

Shoppers watched their food bills rocket and large swathes of the developing world such as North Africa, literally dependent on Ukrainian grain for their survival, experienced political unrest as food prices soared.

The pain has been felt across the food chain and exposed weak points that had hitherto remained untested. For households the most noticeable result of rising gas and oil price rises was bigger fuel bills and more expensive driving, but natural gas is also the key component in the production of ammonium nitrate fertilisers. Its cost became too expensive for many fertiliser plants across Europe to sustain production and they shut down their production lines.

Those farmers able to actually get their hands on some fertiliser were paying more than double the pre-invasion price. In addition, few people realised that the carbon dioxide used, among other things, for stunning animals in abattoirs, keeping packaged food fresh, keg beer under pressure and fizzy drinks sparkling, was also a by-product of fertiliser manufacturing.

At one point the government had to pay a fertiliser producer to keep its plant running just to ensure the country didn’t run dry of this vital gas. Pubs are concerned they won’t be able to keep serving beer.

Survival

For the moment, its about survival with governments around the EU forced to intervene in energy markets to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars, but we are already starting to see more fundamental shifts appear in the countryside, from government policy down to the future cropping plans of farmers and landowners.

Arguably the most public shift in the UK has been the change in emphasis on the issue of food security by the new Prime Minister Liz Truss compared to her predecessor Boris Johnson, who was more focused on the environment. The Ukraine crisis has exacerbated an already heated debate on what farmland should be used for – food, trees, energy or nature.

But the public, media and NGO response to suggestions the government might want to devote fewer resources to its new Environmental Land Management Scheme (Elms), and may even be less committed to its biodiversity and net zero targets, was swift and brutal.

Despite the government’s vehement denial to the contrary, I don’t think it is too farfetched to say the backlash and loss of trust could help to contribute to a change in government at the next general election. It is unfortunate the debate has become so polarised as landowners in the UK can happily deliver both quality food and environmental benefits, not to mention, as discussed below, green energy.

But one change that would surely be welcomed by the electorate is a root-and-branch review of energy markets. As my colleague and renewable energy expert Robert Blake points out, the energy crisis has brought to our attention a fundamental issue with our energy market. Prices are linked to wholesale gas prices, however over 40% of the UK’s power already comes from renewables which are considerably cheaper.

Energy reform

“I’m confident there will be reforms to the energy market, but the general conversation might lead to greater focus from the public on how our energy is generated,” says Robert. “If and when electricity prices are decoupled from gas, will people be more tolerant of on-shore wind turbines if they know they produce the cheapest power?

“The government told us in their April Energy Security Strategy that they are considering offering cheaper power to people who live close to wind turbines, and recently Truss announced that she will make planning easier for on shore wind, which means solar farms, which she seems to loathe, might not be the only option on the table.”

The trend towards a decentralised power network is likely to continue and we are already seeing a surge in people looking at on-site power generation to reduce their exposure to the price fluctuations of power from the grid.

Rural estate owners will, for example, start to think more about providing energy to the communities living around them, believes Jess Waddington of our Rural Consultancy team.

The current energy crunch is definitely focusing the minds of our clients and they are well aware that rural fuel poverty is a growing issue.

I mentioned earlier that Liz Truss’s commitment to the environment has already been questioned, but for a growing number of farmers the Ukrainian crisis has already reinforced the feeling that farming in the UK has to change if it is to remain environmentally sustainable for the long-term.

Techniques such as regenerative agriculture, which rely more on careful soil husbandry than the intensive use of artificial chemicals and fertilisers to produce good crop yields, were already being championed by farmers of an environmental bent. The more than doubling in the cost of fertiliser since the invasion of Ukraine makes adopting them an economic imperative, as well as an environmental one and that momentum looks unlikely to change.

Input costs

“Farmers are certainly reviewing their use of inputs,” confirms Tom Heathcote of Knight Frank’s Agri-consultancy team. “It’s not just chemicals and fertiliser, but also fuel and water. Businesses are trying to work out how they can create more closed and sustainable systems, often in conjunction with better use of technology such as precision farming.”

The high cost of fertiliser could also encourage some farmers to grow fewer acres of nitrogen-hungry crops such as milling wheat, adds Andrew Martin, a colleague of Tom’s, which would make us more dependent on imports. Some though are taking a slightly different approach, he points out. “To avoid being left at the mercy of increasingly volatile markets and risk running out I know of some farming businesses that are investing heavily in extra fuel and fertiliser storage.”

It would be fair to say that the British countryside is in a state of flux that it hasn’t experienced since the Dig for Victory campaign of the Second World War when hundreds of thousands of extra acres went under the plough to help feed the nation. Around eight decades later armed conflict in Europe is once again reshaping our farms and fields.