The future facing rural landowners

Landowners and farmers are at the beginning of a journey into a brave new post-Brexit world that will be greener – and more competitive. Andrew Shirley, Head of Rural Research, surveys the terrain ahead.

7 minutes to read

Brexit

For the first time in a while there is no need for me to make a nervous prediction on these pages that by next issue we will be completely out of the EU. We left. And, despite last-minute jitters, we even managed to secure a trade deal.

And did the sky fall down? If I was a fisherman, Scottish seed potato grower, produce exporter or somebody used to trading freely across the Irish border I might feel that Brexit wasn’t delivering for me. But, by and large, I don’t think many farmers will have noticed much of a difference yet, one way or the other. The results of our Rural Sentiment Survey (see page 18) certainly back that up, so far.

However, it is, of course, still early days, and burgeoning global commodity markets and the Covid-19 pandemic have focused attention elsewhere. It is far too soon to judge whether Brexit will deliver the promised trade deals that will benefit UK agriculture. Those struck so far, with Japan for example, have been symbolically important, but in substance largely similar to the ones we enjoyed before as members of the EU. The US shows no sign of rushing to sign an agreement with us, and farmers have lashed out against the proposed free trade agreement with Australia.

There have been a few early signs that the greater flexibility to govern our own affairs outside the EU could benefit farming businesses. Parliament’s cross-party Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Efra) committee is putting pressure on the government to ensure the public sector buys far more of the food it uses from British farmers now it no longer needs to stick to EU procurement rules.

Meanwhile, Defra Minister George Eustice is keen to unlock the potential of gene editing, currently banned in Europe, although his pronouncement on the subject was met with an instant chorus of disapproval from environmentalists. It has to be said that greater freedom to do what we want can cut both ways when it comes to government policy. As dairy farmers in Wales, now declared a Nitrate Vulnerable Zone (NVZ) in its entirety, will attest, farm regulation will only become stricter.

Support payments

The potential pain will start to ratchet up very soon, though, for those whose businesses rely on the current Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) to stay in the black, which is to say a very large proportion of the UK’s farmers. Area-based support will be reduced incrementally for English claimants until a last cheque in 2027 (a lump sum payment for those who want to retire before then will also be available). The table clearly shows how quickly this could hit the bottom line, with payments cut in half by 2024, and those receiving the biggest cheques seeing the biggest cuts.

Farmers in Scotland and Wales will enjoy slightly less swingeing cuts, to begin with, although no details of what will replace BPS have yet been announced. Scottish livestock farmers are hoping that payments will not be completely disconnected from production, with some kind of area-based payment remaining in place.

The big unanswered question is how much of the lost £3 billion or so of BPS claimed each year by the UK’s farmers can be replaced by the government’s flagship – although still detail-light – Environmental Land Management scheme and other green payments. At a national level, Defra has promised to match fund it, in the short-term at least, but there is absolutely no guarantee that individual farmers will get anywhere near the same amount of money. Although our Sentiment Survey shows only 26% of our respondents believe cuts to BPS will have a “significant” impact on their businesses over the next five years, that is still a concerning number.

The challenge, however, is quantifiable. Unlike the prospect of bad weather or falling commodity prices, claimants know how much they will be losing and over what period. How they resolve the issue, whether it’s through greater efficiencies and innovation, collaboration (environmental support will be greatest for landscape-scale projects), diversification or business restructuring, will be the ultimate Brexit dividend for UK agriculture, which has been held back from exploiting its true entrepreneurial potential by the safety net of subsidy payments.

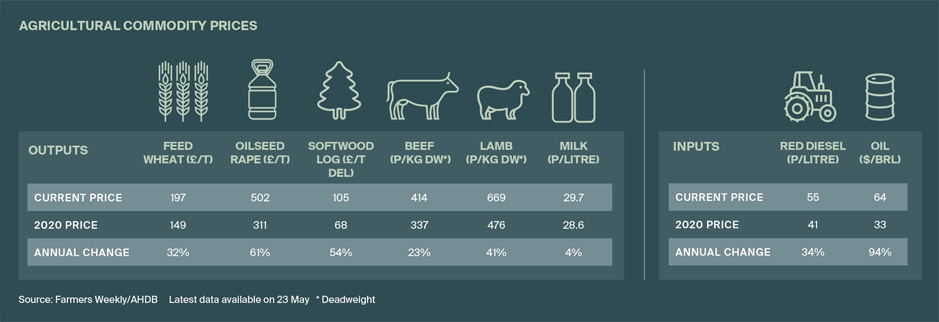

The key will be not using this year’s strong farm commodity markets – see the table opposite for details – as an excuse for kicking the can down the road.

ESG

Despite the trials and tribulations of leaving the EU, it would be a mistake to view Brexit as the defining event shaping the future of agriculture and landownership in the UK. There is, in fact, no defining event, instead an alphabet soup collectively referred to as ESG. This has been building momentum over the past decade or so, and will have the longest-reaching impact on how we farm and manage our land.

Climate change concerns were the forerunner of the ESG – environmental, social and corporate governance – movement. When we first published The Rural Report over a decade ago, renewable energy was the buzzword in rural circles, and to an extent it still is a hot topic (turn to page 18 to find out why), but cutting carbon through a whole host of other measures and protecting the environment now lie at the heart of government policy. The Covid-19 pandemic seems to have only exacerbated this focus.

The Treasury-commissioned Dasgupta Review, published earlier this year, concluded: “Nature needs to enter economic and finance decision-making in the same way buildings, machines, roads and skills do. To do so ultimately requires changing our measures of economic success.”

Easier said than done for a small business, but the government is set to enshrine five internationally recognised environmental principles (see panel) into its eagerly awaited Environment Bill, that will create a duty on ministers when making policy to “[demonstrate] to the world that the environment is at the front and centre of the government’s work, ahead of the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference.

Hitting net zero lies at the heart of this and getting there by the target date of 2050 is now more than a manifesto pledge – the government has made it a binding commitment written into law. It has also signed up to the global 30:30 challenge, committing to devoting 30% of land in England to nature by 2030. Biodiversity offsetting is also now mandatory for any new development.

From a food and farming perspective, however, there seem to be a lot of pledges, commitments and exaltations from the government – eat less meat, rear fewer animals, plant more trees – but little substance as to how any of this can happen while sustaining a profitable agricultural sector able to compete with overseas imports from lower-cost farming systems.

While farmers in other parts of the world are, for example, already selling soil carbon credits to big corporations for big money, the UK’s carbon trading market remains in its infancy. Only new tree planting qualifies, but few farmers want to forest over productive land, and Scotland is the only country in the union that has managed to encourage significant amounts of new woodland creation so far.

Ultimately though, change will come regardless of whether the government paves the way or not. Food retailers and processors are already setting their own ambitious net-zero targets (see panel, right) that will encompass their farming suppliers.

ESG will still be influencing rural businesses once Brexit is a distant memory.

The big five

The government’s environmental principles

1. Integration

Policymakers should look for opportunities to embed environmental protection in other fields of policy.

2. Prevention

Government policy should aim to prevent, reduce or mitigate harm.

3. Rectification at source

If damage to the environment cannot be prevented it should be tackled at its origin.

4. The polluter pays

Those who cause pollution or damage to the environment should be responsible for mitigation or compensation.

5. Precautionary

A lack of scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.