Five reasons why the UK housing market isn’t vulnerable to rising interest rates, for now

From copper to consumer goods, it feels like the price of almost everything is on the rise.

5 minutes to read

The UK consumer price index, which spans cleaning products to clothing, is rising at its fastest pace since before the pandemic. A CBI measure of future price rises in the manufacturing sector is at its highest level since 2018.

This is a global theme. Economies are reopening and consumers are spending, fuelling imbalances between supply and demand. Whether or not central banks should dial back support for the economy, including whether they raise interest rates, are among the most important questions in economics right now.

These are vital decisions for the housing market, too. Rising interest rates can increase mortgage costs and weigh on prices. Last week Sir Jon Cunliffe, the Bank of England’s deputy governor, told the Times that a one percentage point increase in the base rate reduces house prices from somewhere between 2% and 11%.

However, there are a number of reasons why the UK housing market is in a robust position as we move into an environment of rising interest rates. Using Knight Frank Research and insights from experts at Capital Economics and the International Monetary Fund, we’ve compiled the five most compelling reasons why:

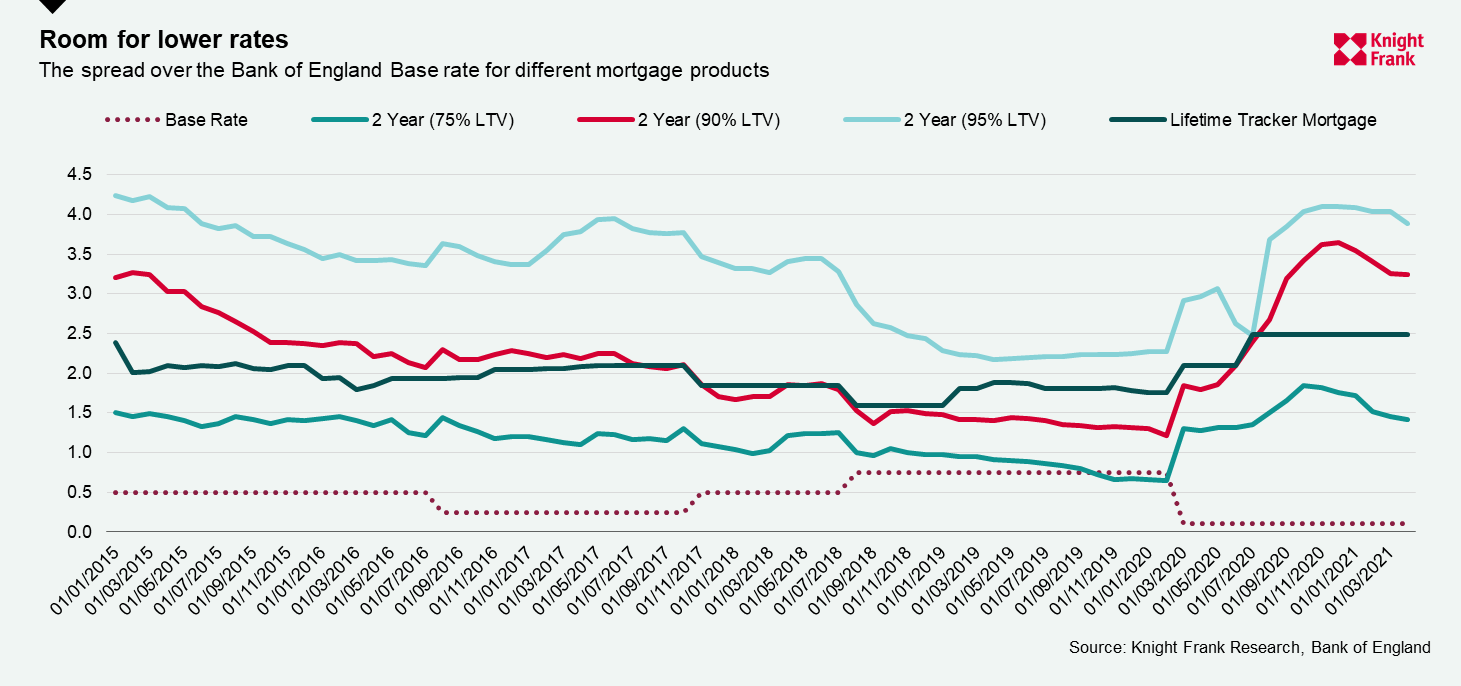

1. Lenders could absorb a rise in interest rates

Banks increased their margins in 2020 in response to heightened economic risks. The difference between the base rate and the rate on mortgage products – also known as the spread – is well above pre-pandemic norms. It’s most notable in higher loan-to-value (LTV) products; the average spread for 2-year products at 90% LTV is 1.2% higher than it was before the pandemic. While this has improved in recent months, it remains at its highest level since 2015.

Any base rate increases could be absorbed by banks by narrowing the spread due to a brighter economic outlook, Andrew Wishart of Capital Economics told me when we spoke last week.

“It’s likely that a rate hike of 25 bps would have little upward pressure on mortgage rates, though the next 75 bps would probably push them up, although by a small amount,” he added.

The Capital Economics baseline forecast is for mortgage rates to fall in the near term and spreads to narrow, with no interest rates rises before 2025.

2. Even if rates did rise, borrowers would still be spending a smaller proportion of their income on mortgage repayments relative to historic norms.

Using a simple model of average lending rates, average incomes and house prices, we know that borrowers are spending approximately 24% of their monthly income on mortgage repayments. If mortgage rates rose by 1%, mirroring a rising in the base rate, that proportion would rise to 27%.

Any increase will be a stretch to some borrowers, however the proportion remains well below historic norms. Back in 2007, for example, borrowers were spending an average 42% of their income on mortgage repayments.

As Mr Wishart notes: “On average, 25% of post-tax income is dedicated to mortgage payments. When it goes much beyond this, we can see a danger of a correction. However, a slight increase, especially when consumers are spending less on commuting, will have a negligible impact”

3. High LTV lending has shrunk

Due to regulations introduced in the wake of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), banks have cut 90% LTV lending to about 4% of total mortgage debt. In 2007 the corresponding figure was almost 16%.

Even if house prices were to correct, there is a smaller part of the market vulnerable to modest declines in house prices, which creates less systemic risk.

This is especially true given that in the Bank of England December Financial Stability report noted that banks’ capital ratio – effectively the funds banks hold relative the assets on their books – increased from 14.8% at end-2019 to 15.8% at end-September. That’s more than three times its pre-GFC level.

So banks have capacity for some credit losses, in the unlikely event house prices were to decline enough to cause a notable increase in arrears.

4. Demand outweighs supply in global housing markets, underpinning prices

The pandemic has pushed excess savings globally to record high levels. In the UK alone, consumers are estimated to have amassed £180 billion during the past twelve months.

Those savings, plus the mass reassessment of lifestyles in the wake of the pandemic at a time when the supply of houses is constrained – a theme we explored in detail here – has exacerbated an imbalance between supply and demand, according to Deniz Igan, Chief of the Systemic Issues Research at the International Monetary Fund.

“There is also a demographics element,” she adds. “A cohort of buyers are now entering the market who want to buy before prices rise further and they can lock in the low interest rates.”

This ongoing imbalance will help to sustain prices, cushioning any blow from increases in interest rates.

5. Any rate rises are likely to be gradual.

In the wake of the GFC the Bank of England did not move rates until 2016, when it lowered them in response to the Brexit vote. A year later they rose 25bps, followed by another 25bps less than a year later. The Bank tends to move cautiously – especially compared to its US counterpart, which began raising rates in 2015 and subsequently raised them 225 bps in three years.

It’s also possible rates remain low relative to historic norms for the foreseeable. Indeed, lower real interest rates may become a permanent fixture in major economies due to slowing population growth across the globe, according to a growing number of market watchers that include US investment bank JP Morgan.

However, this crisis and subsequent recovery is playing out differently to the GFC, largely to the size, scope and speed of the bounce-back. It is not beyond the realms of possibility that the Bank is pressured to act faster than any of its Monetary Policy Committee currently expect.

“Globally, the relationship between interest rates and house prices has strengthened in the past year,” Igan says. “Our model now shows that across 30 or so countries, rates are more important [than they have been historically] for determining house prices and a 100-bps change would have a 1.5-2% impact on house prices.”

On balance, a mixture of factors including elevated mortgage lending margins, robust demand relative to supply and a greater proportion of lower LTV lending means the UK is in a robust position as we move into an environment of tighter monetary policy, regardless of how long central bankers hold their nerve.